Oct 16, 2021

Incoterms: A complete guide

A simple explanation of the most widely commercial terms in global trade.

Let's say you're a buyer, and just found a great seller, negotiated a price, and shook hands. Success!

Now what? "Are you going to ship? Or should I organize it?" And "what happens if the goods are destroyed in transit, is that your problem or mine?"

These are age-old trade questions that Incoterms answer.

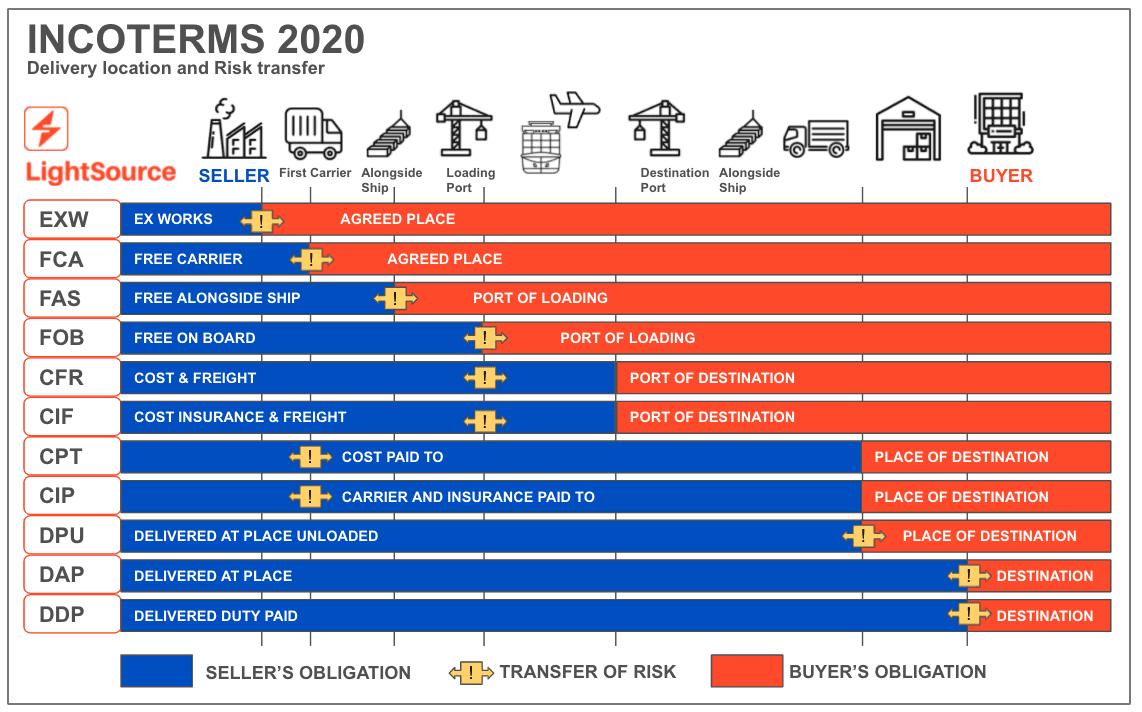

Incoterms (short for "International Commercial Terms") are a set of 11 commercial terms that govern logistics

liability in global trade. They are defined by the International Chamber of Commerce, and are published once per decade (most recently in 2020).

They describe two primary responsibilities:

1. Who covers the cost of logistics? The buyer or the seller.

2. Who is liable for the risks in transit? Like damage or loss.

Collectively, the terms cover all modes of transportation -- road, rail, air, and sea -- but some terms are specific to certain modes. For example, FAS ("Free Alongside Ship") only applies to sea freight, while DDP ("Delivered Duty Paid") means the seller will deliver the goods with duties paid, regardless of mode of transport.

At first glance, Incoterms seem complex, but once you get the gist, they're second-nature. Moreover, in practice most companies will use largely one chosen Incoterm for all commercial agreements to keep things simple.

Let's dive in:

The 11 Incoterms

EXW - Ex works (named place of delivery)

The seller makes the goods available at their premises, typically the "named place". This term places virtually all responsibility on the buyer. Put simple, the seller just gets the "stuff out the door" and has no obligation beyond that.

Ex Works term is often used in initial rounds of quoting because it reflects the cost of good without logistics. While this is outside their contractual obligations, sellers will sometimes still help arrange carriage or other customs documents. Communication is key, though, as this is not required of them.

FCA - Free carrier (named place of delivery)

Under Free Carrier the seller is responsible to deliver the goods to a "named place" (typically their premises) and cleared for export. FCA is a common term and has largely replaced FOB (freight on board), with the distinction that the seller is not responsible for loading goods onto the buyer's carrier.

If the delivery is the seller's premises, they are responsible for loading the goods. If the named place is anywhere else, just delivery is sufficient to satisfy the seller's obligations.

FAS – Free alongside ship (named port of shipment), sea-only

Seller delivers when the goods are placed alongside the buyer's vessel at the named port of shipment. This Incoterm by definition only applies to seafreight or inland waterway transport,. By contrast EXW, FCA, CPT, CIP, DPU, DAP, and DDP apply to all modes of transportation.

FOB – Free on board (named port of shipment), sea-only

Seller delivers the good onto the vessel, and are responsible for all costs and risks up until that point. Technically, FOB should only be used for sea freight, however it's often incorrectly usd for all modes. In some countries, such as the United States, FOB can be used in connection with carriage of good by any vessel, including cars and trucks.

CFR – Cost and freight (named port of destination), sea-only

Seller responsible for the cost of freight until the destination port. However, this is the first time where the cost and risk obligation split. While responsible for the cost of freight, the seller is only responsible for risks until the goods are loaded onto the vessel in the country of export.

This is equivalent to the seller saying: "sure, I'll pay for shipping, but if something gets damaged in shipping, it's not my problem."

CIF – Cost, insurance & freight (named port of destination), sea-only

CIF is similar to CFR except it contractually requires the seller to also insure the shipment for 110% of the contract value. CIF should only be used for _non-containerized_ sea freight. Other modes of transportation should use CIP instead.

CPT – Carriage paid to (named place of destination)

Seller pays the carriage of goods until the "named place" of destination. However, the risk risk transfers to the buyer earlier: once handed over to the carrier at the export.

CIP – Carriage and insurance Paid to (named place of destination)

CIP is similar to CPT except again it requires the seller to insure the shipment. It can be used for all modes of transportation, except non-containerized sea freight (refer to CIF).

DPU – Delivered at place unloaded (named place of destination)

Seller is required to deliver the goods, unloaded, at the named place destination. The seller covers all the costs of transport (including carriage, export fees, and unloading) and assumes risks until arrival there.

One nuance here is the around the definition of "unloaded." Be sure to explicitly discuss with your trade partner when dealing with containerized shipments over whether the intention is unloaded from the vessel or unloaded from the container also once offboard.

DAP – Delivered at place (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for the deliver of goods at a named place. Typically the buyer is responsible for import documentations and all customs, duties, and taxes.

DDP – Delivered duty paid (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for the whole enchilada - delivery of goods to the named place in the country of the buyer, paying all costs including carriage as well as import duties and taxes.

This term represents the maximum responsibility to sellers and minimum to buyers characterized in the Incoterm 2020 standards. The buyer still however does have the obligation for unloading. The most important consideration here is that the seller is responsible also for the customs clearance of goods - from both the cost and risk standpoint.

When shipping internationally, DDP can pose undue risk if the seller unfamiliar with the destination country's customs and import practices.

Definitions

Within the Incoterms above, there are certain words with specified meanings worth understanding:

Delivery: The point in the transaction where the risk of loss or damage to the goods is transferred from the seller to the buyer

Arrival: The point named in the Incoterm to which carriage has been paid

Free: Seller has an obligation to deliver the goods to a named place for transfer to a carrier

Carrier: Any person or group undertakes a carriage contract to transport good by rail, road, air, sea, inland waterway or any combination of such modes

Freight forwarder: A firm that makes or assists in the making of shipping arrangements

Terminal: Any place, such as a dock, warehouse, container yard or road, rail or air cargo terminal

To clear for export: To file Shipper’s Export Declaration and get export permit

Why do Incoterms matter?

Incoterms are an important element in any commercial interaction related to physical goods. The terms are important understand better what a seller is proposing in terms of cost and liability.

If you have a sourcing project, where one supplier quotes using EXW and another DDP, it could be that one is a radically "better deal" even if the bids look similar at first glance. When buying internationally, the difference between one letter DAP and DDP could be the difference of up to 25% in cost, depending on the tariff codes and rates for the given goods.

At the executive level, a candid conversation around Incoterm strategy is important for the Chief Procurement Officer or VP of Supply Chain to set a standard for risk through logistics. And while rare, things can happen (remember that container ship that got stuck in the Suez canal). So when goods get stuck, lost, or destroyed mid-transit, you'll have to look at your Incoterms to figure out who's problem it is to fix.

Which Incoterms should I choose?

There is no right answer to this question. However, understanding Incoterms is critically important for any supply chain manager.

Depending on the organization, there may be an overall supply chain strategy around Incoterms. For example, back at Tesla, we would typically ask our suppliers to ship goods with the FCA (Free Carrier) term, where we were responsible for the costs and risks of shipping. We chose this for a few reasons:

Logistics visibility: by owning the shipping ourselves we had better visibility into where shipments were in process and what parts they included.

Risk reactivity: when something was "going wrong," we owned the relationship with the carrier on both ends and could more easily take action or expedite a shipment if needed.

Cost transparency: owning logistics meant we knew exactly how much it cost us. When you hand of the responsibility, you don't always know that you're getting a fair price (or that the supplier is getting a fair price from their freight forwarders). Moreover, by feeling the pain directly of shipping costs, it added an incentive for us to rethink cost opportunities like densifying packaging, nesting, and choosing more optimal lanes, while bulking shipments across potentially multiple suppliers.

For these costs reasons, I'd say over 90% of the time, we opted for an FCA or equivalent Incoterm. However, we weren't totally dogmatic either. Sometimes we'd find some larger Tier 1 suppliers were actually able to provide the parts landed at a lower cost than our own internal logistics team could achieve. Maybe they were getting better rates from carriers. Either way, in those cases where either costs were lower or a supplier strongly pushed to own logistics, we could concede to DAP or DDP.

If you have a question about Incoterms, feel free to reach out to us and schedule a meeting.

How to put Incoterms into practice in sales sontracts

There are three steps to put Incoterms into practice:

Agree with your supplier / buyer on the desired Incoterm

Make sure you're all using the same terminology

Write it into your contracts properly

Negotiating Incoterms

LightSource was designed with commercial terms like Incoterms in mind from day-one. When engaging a supplier in a sourcing event, make it clear through the RFQ notes or 1-on-1 message thread that you have a specific Incoterm in mind.

You can alternatively allow multiple suppliers to quote with the Incoterm that they most prefer, and then in the LightSource Bid Comparison tool you'll be able to see differences in commercial terms as well as their cost implications for the buyer.

Once you agree on an Incoterm, typically a buyer/supplier will want to keep the same one throughout the entire book of business between them.

Get on the same page!

This is a simple one, but make sure everyone is in agreement to use the Incoterms 2020 standard. The previous Incoterms 2010 standard applied up to December 31st, 2019. In general, most suppliers and buyers are savvy to the latest set of terms, but worth always checking to make sure everyone is applying the 2020 (and beyond) standard.

Contractual language

This is the structure that should be used in contracts

(Incoterm) (Named Place) "Incoterms 2020"

For example:

FOB Shanghai, China Incoterms 2020

CIF Longbeach Incoterms 2020

DPU 4300 Longbeach Blvd, Longbeach, United States Incoterms 2020

Beyond that, the Incoterm should also be communicated through the Purchase Orders (PO's) and Invoices issues through the ERP or P2P systems. Having best-of-breed supply chain software systems can be as important as best-of-breed practices. So make sure your data is consistent so your team can go into conversations and operations with the best possible information.

Disclaimer

This post should be taken as guidance, but not gospel. LightSource Labs Inc is a software company, and not a logistics broker (and certainly not an international trade law firm). So our recommendation is treat this as an education resource, but if you have a any questions around Incoterms, consult with first your global trade team, legal counsel, or go directly to the ICC for a literal reading of the Incoterm documents directly.

Questions about Incoterms directly answered in this article:

What are Incoterms, and what do they define in global trade?

How many Incoterms exist, and what are the two main responsibilities they govern?

Why do Incoterms matter for direct procurement professionals, especially when comparing supplier quotes?

Which Incoterms are used for all modes of transportation, and which are specific to sea freight?

What is the difference between "Cost and Freight" (CFR) and "Cost, Insurance & Freight" (CIF)?

How does a company's Incoterm strategy impact logistics visibility, cost transparency, and risk management?

What are the three steps for correctly implementing an Incoterm in a sales contract?

How can using different Incoterms for supplier quotes create significant cost differences?

What is the difference between the EXW and DDP Incoterms in terms of seller responsibility?

Let's say you're a buyer, and just found a great seller, negotiated a price, and shook hands. Success!

Now what? "Are you going to ship? Or should I organize it?" And "what happens if the goods are destroyed in transit, is that your problem or mine?"

These are age-old trade questions that Incoterms answer.

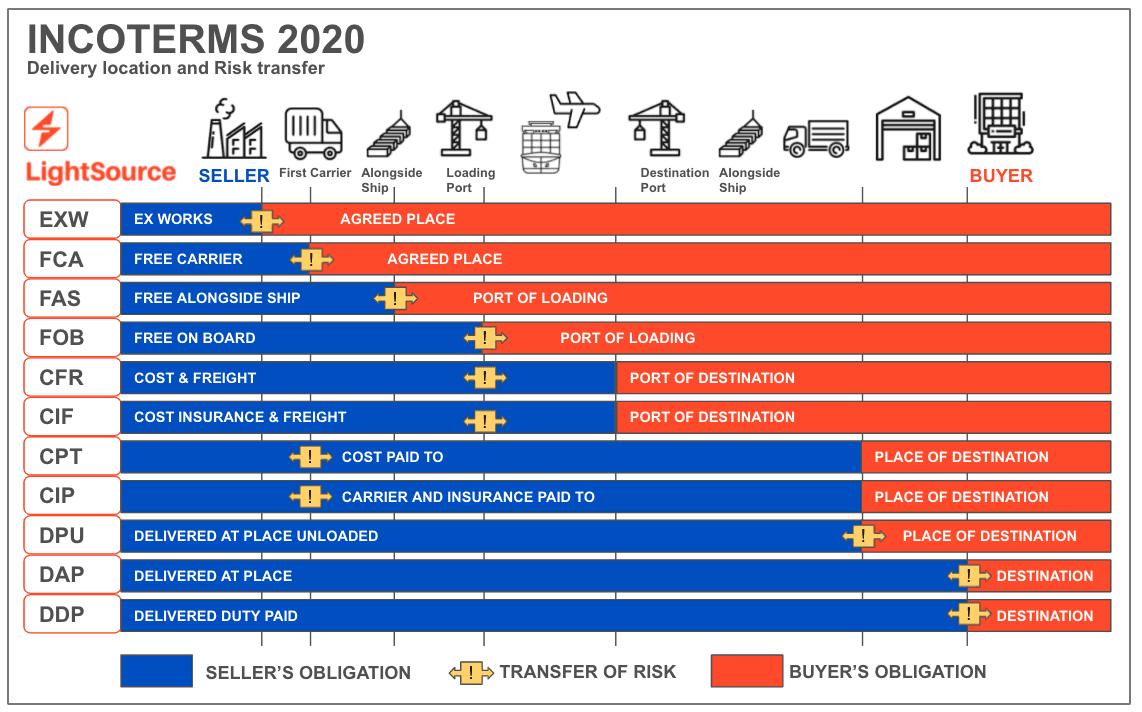

Incoterms (short for "International Commercial Terms") are a set of 11 commercial terms that govern logistics

liability in global trade. They are defined by the International Chamber of Commerce, and are published once per decade (most recently in 2020).

They describe two primary responsibilities:

1. Who covers the cost of logistics? The buyer or the seller.

2. Who is liable for the risks in transit? Like damage or loss.

Collectively, the terms cover all modes of transportation -- road, rail, air, and sea -- but some terms are specific to certain modes. For example, FAS ("Free Alongside Ship") only applies to sea freight, while DDP ("Delivered Duty Paid") means the seller will deliver the goods with duties paid, regardless of mode of transport.

At first glance, Incoterms seem complex, but once you get the gist, they're second-nature. Moreover, in practice most companies will use largely one chosen Incoterm for all commercial agreements to keep things simple.

Let's dive in:

The 11 Incoterms

EXW - Ex works (named place of delivery)

The seller makes the goods available at their premises, typically the "named place". This term places virtually all responsibility on the buyer. Put simple, the seller just gets the "stuff out the door" and has no obligation beyond that.

Ex Works term is often used in initial rounds of quoting because it reflects the cost of good without logistics. While this is outside their contractual obligations, sellers will sometimes still help arrange carriage or other customs documents. Communication is key, though, as this is not required of them.

FCA - Free carrier (named place of delivery)

Under Free Carrier the seller is responsible to deliver the goods to a "named place" (typically their premises) and cleared for export. FCA is a common term and has largely replaced FOB (freight on board), with the distinction that the seller is not responsible for loading goods onto the buyer's carrier.

If the delivery is the seller's premises, they are responsible for loading the goods. If the named place is anywhere else, just delivery is sufficient to satisfy the seller's obligations.

FAS – Free alongside ship (named port of shipment), sea-only

Seller delivers when the goods are placed alongside the buyer's vessel at the named port of shipment. This Incoterm by definition only applies to seafreight or inland waterway transport,. By contrast EXW, FCA, CPT, CIP, DPU, DAP, and DDP apply to all modes of transportation.

FOB – Free on board (named port of shipment), sea-only

Seller delivers the good onto the vessel, and are responsible for all costs and risks up until that point. Technically, FOB should only be used for sea freight, however it's often incorrectly usd for all modes. In some countries, such as the United States, FOB can be used in connection with carriage of good by any vessel, including cars and trucks.

CFR – Cost and freight (named port of destination), sea-only

Seller responsible for the cost of freight until the destination port. However, this is the first time where the cost and risk obligation split. While responsible for the cost of freight, the seller is only responsible for risks until the goods are loaded onto the vessel in the country of export.

This is equivalent to the seller saying: "sure, I'll pay for shipping, but if something gets damaged in shipping, it's not my problem."

CIF – Cost, insurance & freight (named port of destination), sea-only

CIF is similar to CFR except it contractually requires the seller to also insure the shipment for 110% of the contract value. CIF should only be used for _non-containerized_ sea freight. Other modes of transportation should use CIP instead.

CPT – Carriage paid to (named place of destination)

Seller pays the carriage of goods until the "named place" of destination. However, the risk risk transfers to the buyer earlier: once handed over to the carrier at the export.

CIP – Carriage and insurance Paid to (named place of destination)

CIP is similar to CPT except again it requires the seller to insure the shipment. It can be used for all modes of transportation, except non-containerized sea freight (refer to CIF).

DPU – Delivered at place unloaded (named place of destination)

Seller is required to deliver the goods, unloaded, at the named place destination. The seller covers all the costs of transport (including carriage, export fees, and unloading) and assumes risks until arrival there.

One nuance here is the around the definition of "unloaded." Be sure to explicitly discuss with your trade partner when dealing with containerized shipments over whether the intention is unloaded from the vessel or unloaded from the container also once offboard.

DAP – Delivered at place (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for the deliver of goods at a named place. Typically the buyer is responsible for import documentations and all customs, duties, and taxes.

DDP – Delivered duty paid (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for the whole enchilada - delivery of goods to the named place in the country of the buyer, paying all costs including carriage as well as import duties and taxes.

This term represents the maximum responsibility to sellers and minimum to buyers characterized in the Incoterm 2020 standards. The buyer still however does have the obligation for unloading. The most important consideration here is that the seller is responsible also for the customs clearance of goods - from both the cost and risk standpoint.

When shipping internationally, DDP can pose undue risk if the seller unfamiliar with the destination country's customs and import practices.

Definitions

Within the Incoterms above, there are certain words with specified meanings worth understanding:

Delivery: The point in the transaction where the risk of loss or damage to the goods is transferred from the seller to the buyer

Arrival: The point named in the Incoterm to which carriage has been paid

Free: Seller has an obligation to deliver the goods to a named place for transfer to a carrier

Carrier: Any person or group undertakes a carriage contract to transport good by rail, road, air, sea, inland waterway or any combination of such modes

Freight forwarder: A firm that makes or assists in the making of shipping arrangements

Terminal: Any place, such as a dock, warehouse, container yard or road, rail or air cargo terminal

To clear for export: To file Shipper’s Export Declaration and get export permit

Why do Incoterms matter?

Incoterms are an important element in any commercial interaction related to physical goods. The terms are important understand better what a seller is proposing in terms of cost and liability.

If you have a sourcing project, where one supplier quotes using EXW and another DDP, it could be that one is a radically "better deal" even if the bids look similar at first glance. When buying internationally, the difference between one letter DAP and DDP could be the difference of up to 25% in cost, depending on the tariff codes and rates for the given goods.

At the executive level, a candid conversation around Incoterm strategy is important for the Chief Procurement Officer or VP of Supply Chain to set a standard for risk through logistics. And while rare, things can happen (remember that container ship that got stuck in the Suez canal). So when goods get stuck, lost, or destroyed mid-transit, you'll have to look at your Incoterms to figure out who's problem it is to fix.

Which Incoterms should I choose?

There is no right answer to this question. However, understanding Incoterms is critically important for any supply chain manager.

Depending on the organization, there may be an overall supply chain strategy around Incoterms. For example, back at Tesla, we would typically ask our suppliers to ship goods with the FCA (Free Carrier) term, where we were responsible for the costs and risks of shipping. We chose this for a few reasons:

Logistics visibility: by owning the shipping ourselves we had better visibility into where shipments were in process and what parts they included.

Risk reactivity: when something was "going wrong," we owned the relationship with the carrier on both ends and could more easily take action or expedite a shipment if needed.

Cost transparency: owning logistics meant we knew exactly how much it cost us. When you hand of the responsibility, you don't always know that you're getting a fair price (or that the supplier is getting a fair price from their freight forwarders). Moreover, by feeling the pain directly of shipping costs, it added an incentive for us to rethink cost opportunities like densifying packaging, nesting, and choosing more optimal lanes, while bulking shipments across potentially multiple suppliers.

For these costs reasons, I'd say over 90% of the time, we opted for an FCA or equivalent Incoterm. However, we weren't totally dogmatic either. Sometimes we'd find some larger Tier 1 suppliers were actually able to provide the parts landed at a lower cost than our own internal logistics team could achieve. Maybe they were getting better rates from carriers. Either way, in those cases where either costs were lower or a supplier strongly pushed to own logistics, we could concede to DAP or DDP.

If you have a question about Incoterms, feel free to reach out to us and schedule a meeting.

How to put Incoterms into practice in sales sontracts

There are three steps to put Incoterms into practice:

Agree with your supplier / buyer on the desired Incoterm

Make sure you're all using the same terminology

Write it into your contracts properly

Negotiating Incoterms

LightSource was designed with commercial terms like Incoterms in mind from day-one. When engaging a supplier in a sourcing event, make it clear through the RFQ notes or 1-on-1 message thread that you have a specific Incoterm in mind.

You can alternatively allow multiple suppliers to quote with the Incoterm that they most prefer, and then in the LightSource Bid Comparison tool you'll be able to see differences in commercial terms as well as their cost implications for the buyer.

Once you agree on an Incoterm, typically a buyer/supplier will want to keep the same one throughout the entire book of business between them.

Get on the same page!

This is a simple one, but make sure everyone is in agreement to use the Incoterms 2020 standard. The previous Incoterms 2010 standard applied up to December 31st, 2019. In general, most suppliers and buyers are savvy to the latest set of terms, but worth always checking to make sure everyone is applying the 2020 (and beyond) standard.

Contractual language

This is the structure that should be used in contracts

(Incoterm) (Named Place) "Incoterms 2020"

For example:

FOB Shanghai, China Incoterms 2020

CIF Longbeach Incoterms 2020

DPU 4300 Longbeach Blvd, Longbeach, United States Incoterms 2020

Beyond that, the Incoterm should also be communicated through the Purchase Orders (PO's) and Invoices issues through the ERP or P2P systems. Having best-of-breed supply chain software systems can be as important as best-of-breed practices. So make sure your data is consistent so your team can go into conversations and operations with the best possible information.

Disclaimer

This post should be taken as guidance, but not gospel. LightSource Labs Inc is a software company, and not a logistics broker (and certainly not an international trade law firm). So our recommendation is treat this as an education resource, but if you have a any questions around Incoterms, consult with first your global trade team, legal counsel, or go directly to the ICC for a literal reading of the Incoterm documents directly.

Questions about Incoterms directly answered in this article:

What are Incoterms, and what do they define in global trade?

How many Incoterms exist, and what are the two main responsibilities they govern?

Why do Incoterms matter for direct procurement professionals, especially when comparing supplier quotes?

Which Incoterms are used for all modes of transportation, and which are specific to sea freight?

What is the difference between "Cost and Freight" (CFR) and "Cost, Insurance & Freight" (CIF)?

How does a company's Incoterm strategy impact logistics visibility, cost transparency, and risk management?

What are the three steps for correctly implementing an Incoterm in a sales contract?

How can using different Incoterms for supplier quotes create significant cost differences?

What is the difference between the EXW and DDP Incoterms in terms of seller responsibility?

Let's say you're a buyer, and just found a great seller, negotiated a price, and shook hands. Success!

Now what? "Are you going to ship? Or should I organize it?" And "what happens if the goods are destroyed in transit, is that your problem or mine?"

These are age-old trade questions that Incoterms answer.

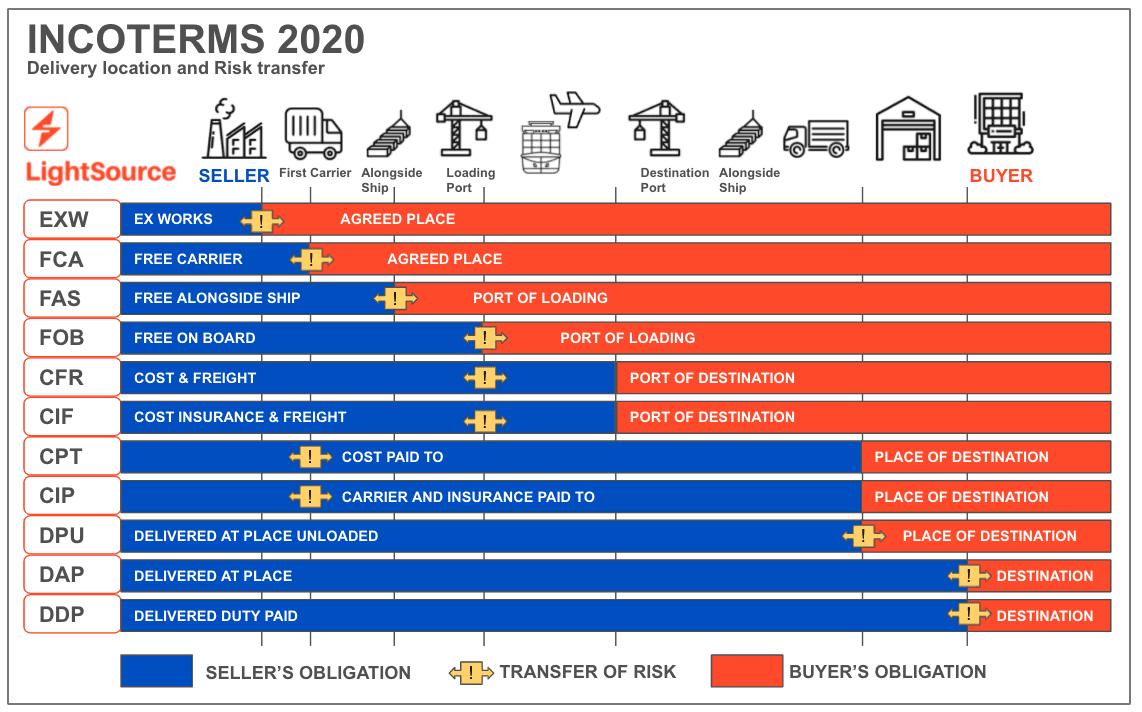

Incoterms (short for "International Commercial Terms") are a set of 11 commercial terms that govern logistics

liability in global trade. They are defined by the International Chamber of Commerce, and are published once per decade (most recently in 2020).

They describe two primary responsibilities:

1. Who covers the cost of logistics? The buyer or the seller.

2. Who is liable for the risks in transit? Like damage or loss.

Collectively, the terms cover all modes of transportation -- road, rail, air, and sea -- but some terms are specific to certain modes. For example, FAS ("Free Alongside Ship") only applies to sea freight, while DDP ("Delivered Duty Paid") means the seller will deliver the goods with duties paid, regardless of mode of transport.

At first glance, Incoterms seem complex, but once you get the gist, they're second-nature. Moreover, in practice most companies will use largely one chosen Incoterm for all commercial agreements to keep things simple.

Let's dive in:

The 11 Incoterms

EXW - Ex works (named place of delivery)

The seller makes the goods available at their premises, typically the "named place". This term places virtually all responsibility on the buyer. Put simple, the seller just gets the "stuff out the door" and has no obligation beyond that.

Ex Works term is often used in initial rounds of quoting because it reflects the cost of good without logistics. While this is outside their contractual obligations, sellers will sometimes still help arrange carriage or other customs documents. Communication is key, though, as this is not required of them.

FCA - Free carrier (named place of delivery)

Under Free Carrier the seller is responsible to deliver the goods to a "named place" (typically their premises) and cleared for export. FCA is a common term and has largely replaced FOB (freight on board), with the distinction that the seller is not responsible for loading goods onto the buyer's carrier.

If the delivery is the seller's premises, they are responsible for loading the goods. If the named place is anywhere else, just delivery is sufficient to satisfy the seller's obligations.

FAS – Free alongside ship (named port of shipment), sea-only

Seller delivers when the goods are placed alongside the buyer's vessel at the named port of shipment. This Incoterm by definition only applies to seafreight or inland waterway transport,. By contrast EXW, FCA, CPT, CIP, DPU, DAP, and DDP apply to all modes of transportation.

FOB – Free on board (named port of shipment), sea-only

Seller delivers the good onto the vessel, and are responsible for all costs and risks up until that point. Technically, FOB should only be used for sea freight, however it's often incorrectly usd for all modes. In some countries, such as the United States, FOB can be used in connection with carriage of good by any vessel, including cars and trucks.

CFR – Cost and freight (named port of destination), sea-only

Seller responsible for the cost of freight until the destination port. However, this is the first time where the cost and risk obligation split. While responsible for the cost of freight, the seller is only responsible for risks until the goods are loaded onto the vessel in the country of export.

This is equivalent to the seller saying: "sure, I'll pay for shipping, but if something gets damaged in shipping, it's not my problem."

CIF – Cost, insurance & freight (named port of destination), sea-only

CIF is similar to CFR except it contractually requires the seller to also insure the shipment for 110% of the contract value. CIF should only be used for _non-containerized_ sea freight. Other modes of transportation should use CIP instead.

CPT – Carriage paid to (named place of destination)

Seller pays the carriage of goods until the "named place" of destination. However, the risk risk transfers to the buyer earlier: once handed over to the carrier at the export.

CIP – Carriage and insurance Paid to (named place of destination)

CIP is similar to CPT except again it requires the seller to insure the shipment. It can be used for all modes of transportation, except non-containerized sea freight (refer to CIF).

DPU – Delivered at place unloaded (named place of destination)

Seller is required to deliver the goods, unloaded, at the named place destination. The seller covers all the costs of transport (including carriage, export fees, and unloading) and assumes risks until arrival there.

One nuance here is the around the definition of "unloaded." Be sure to explicitly discuss with your trade partner when dealing with containerized shipments over whether the intention is unloaded from the vessel or unloaded from the container also once offboard.

DAP – Delivered at place (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for the deliver of goods at a named place. Typically the buyer is responsible for import documentations and all customs, duties, and taxes.

DDP – Delivered duty paid (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for the whole enchilada - delivery of goods to the named place in the country of the buyer, paying all costs including carriage as well as import duties and taxes.

This term represents the maximum responsibility to sellers and minimum to buyers characterized in the Incoterm 2020 standards. The buyer still however does have the obligation for unloading. The most important consideration here is that the seller is responsible also for the customs clearance of goods - from both the cost and risk standpoint.

When shipping internationally, DDP can pose undue risk if the seller unfamiliar with the destination country's customs and import practices.

Definitions

Within the Incoterms above, there are certain words with specified meanings worth understanding:

Delivery: The point in the transaction where the risk of loss or damage to the goods is transferred from the seller to the buyer

Arrival: The point named in the Incoterm to which carriage has been paid

Free: Seller has an obligation to deliver the goods to a named place for transfer to a carrier

Carrier: Any person or group undertakes a carriage contract to transport good by rail, road, air, sea, inland waterway or any combination of such modes

Freight forwarder: A firm that makes or assists in the making of shipping arrangements

Terminal: Any place, such as a dock, warehouse, container yard or road, rail or air cargo terminal

To clear for export: To file Shipper’s Export Declaration and get export permit

Why do Incoterms matter?

Incoterms are an important element in any commercial interaction related to physical goods. The terms are important understand better what a seller is proposing in terms of cost and liability.

If you have a sourcing project, where one supplier quotes using EXW and another DDP, it could be that one is a radically "better deal" even if the bids look similar at first glance. When buying internationally, the difference between one letter DAP and DDP could be the difference of up to 25% in cost, depending on the tariff codes and rates for the given goods.

At the executive level, a candid conversation around Incoterm strategy is important for the Chief Procurement Officer or VP of Supply Chain to set a standard for risk through logistics. And while rare, things can happen (remember that container ship that got stuck in the Suez canal). So when goods get stuck, lost, or destroyed mid-transit, you'll have to look at your Incoterms to figure out who's problem it is to fix.

Which Incoterms should I choose?

There is no right answer to this question. However, understanding Incoterms is critically important for any supply chain manager.

Depending on the organization, there may be an overall supply chain strategy around Incoterms. For example, back at Tesla, we would typically ask our suppliers to ship goods with the FCA (Free Carrier) term, where we were responsible for the costs and risks of shipping. We chose this for a few reasons:

Logistics visibility: by owning the shipping ourselves we had better visibility into where shipments were in process and what parts they included.

Risk reactivity: when something was "going wrong," we owned the relationship with the carrier on both ends and could more easily take action or expedite a shipment if needed.

Cost transparency: owning logistics meant we knew exactly how much it cost us. When you hand of the responsibility, you don't always know that you're getting a fair price (or that the supplier is getting a fair price from their freight forwarders). Moreover, by feeling the pain directly of shipping costs, it added an incentive for us to rethink cost opportunities like densifying packaging, nesting, and choosing more optimal lanes, while bulking shipments across potentially multiple suppliers.

For these costs reasons, I'd say over 90% of the time, we opted for an FCA or equivalent Incoterm. However, we weren't totally dogmatic either. Sometimes we'd find some larger Tier 1 suppliers were actually able to provide the parts landed at a lower cost than our own internal logistics team could achieve. Maybe they were getting better rates from carriers. Either way, in those cases where either costs were lower or a supplier strongly pushed to own logistics, we could concede to DAP or DDP.

If you have a question about Incoterms, feel free to reach out to us and schedule a meeting.

How to put Incoterms into practice in sales sontracts

There are three steps to put Incoterms into practice:

Agree with your supplier / buyer on the desired Incoterm

Make sure you're all using the same terminology

Write it into your contracts properly

Negotiating Incoterms

LightSource was designed with commercial terms like Incoterms in mind from day-one. When engaging a supplier in a sourcing event, make it clear through the RFQ notes or 1-on-1 message thread that you have a specific Incoterm in mind.

You can alternatively allow multiple suppliers to quote with the Incoterm that they most prefer, and then in the LightSource Bid Comparison tool you'll be able to see differences in commercial terms as well as their cost implications for the buyer.

Once you agree on an Incoterm, typically a buyer/supplier will want to keep the same one throughout the entire book of business between them.

Get on the same page!

This is a simple one, but make sure everyone is in agreement to use the Incoterms 2020 standard. The previous Incoterms 2010 standard applied up to December 31st, 2019. In general, most suppliers and buyers are savvy to the latest set of terms, but worth always checking to make sure everyone is applying the 2020 (and beyond) standard.

Contractual language

This is the structure that should be used in contracts

(Incoterm) (Named Place) "Incoterms 2020"

For example:

FOB Shanghai, China Incoterms 2020

CIF Longbeach Incoterms 2020

DPU 4300 Longbeach Blvd, Longbeach, United States Incoterms 2020

Beyond that, the Incoterm should also be communicated through the Purchase Orders (PO's) and Invoices issues through the ERP or P2P systems. Having best-of-breed supply chain software systems can be as important as best-of-breed practices. So make sure your data is consistent so your team can go into conversations and operations with the best possible information.

Disclaimer

This post should be taken as guidance, but not gospel. LightSource Labs Inc is a software company, and not a logistics broker (and certainly not an international trade law firm). So our recommendation is treat this as an education resource, but if you have a any questions around Incoterms, consult with first your global trade team, legal counsel, or go directly to the ICC for a literal reading of the Incoterm documents directly.

Questions about Incoterms directly answered in this article:

What are Incoterms, and what do they define in global trade?

How many Incoterms exist, and what are the two main responsibilities they govern?

Why do Incoterms matter for direct procurement professionals, especially when comparing supplier quotes?

Which Incoterms are used for all modes of transportation, and which are specific to sea freight?

What is the difference between "Cost and Freight" (CFR) and "Cost, Insurance & Freight" (CIF)?

How does a company's Incoterm strategy impact logistics visibility, cost transparency, and risk management?

What are the three steps for correctly implementing an Incoterm in a sales contract?

How can using different Incoterms for supplier quotes create significant cost differences?

What is the difference between the EXW and DDP Incoterms in terms of seller responsibility?

Ready to change the way you source?

Try out LightSource and you’ll never go back to Excel and email.

Ready to change the way you source?

Try out LightSource and you’ll never go back to Excel and email.

Ready to change the way you source?

Try out LightSource and you’ll never go back to Excel and email.

Trusted by:

Trusted by:

Trusted by:

*GARTNER is a registered trademark and service mark of Gartner, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the U.S. and internationally, and COOL VENDORS is a registered trademark of Gartner, Inc. and/or its affiliates and are used herein with permission. All rights reserved. Gartner does not endorse any vendor, product or service depicted in its research publications, and does not advise technology users to select only those vendors with the highest ratings or other designation. Gartner research publications consist of the opinions of Gartner’s research organization and should not be construed as statements of fact. Gartner disclaims all warranties, expressed or implied, with respect to this research, including any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose.